What Is More Important, Materials or Form?

Would the Villa Rotonda look good made of cheese?

When faced with a client whose budget demands cheap materials, I am comforted by the thought that Palladio had to deal with these exact challenges. All his villas in the Veneto are made from render which is a cheaper alternative to stone, but it looks similar from a distance, which makes me think that even if the Villa Rotonda was made of cheese, it would still look splendid from afar - sitting majestically on a hill outside Vicenza. Sometimes this can be forgotten by an architect as your dream stone house, becomes ‘reconstructed stone’ (which is little more than well-marketed precast concrete) or your beautifully detailed hardwood sash windows become PVC double glazed units. These are client choices and part of the architect’s art is to choose wisely when faced with such compromises.

Some architects argue that the use of good materials and sound construction is what makes good architecture. Some of my classical friends are very insistent that their work is always constructed from load-bearing masonry and constructed from good quality materials. But what do you do when the budget does not allow for such luxuries?

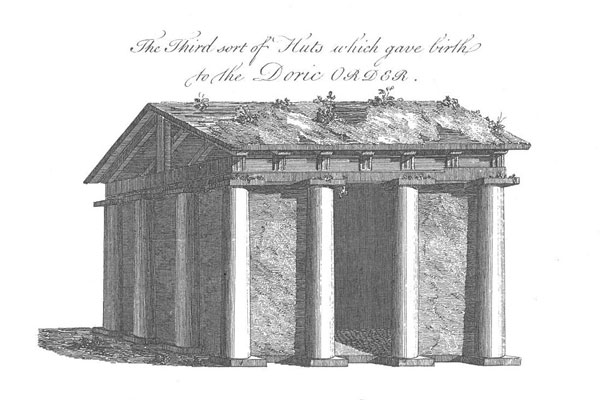

The idea that good architecture is essential to good construction has a long history, going back to Vitruvius, but it returned with vigour in the mid 18th century when the Neo-Classicists reacted against the extravagant excesses of the baroque. Laugier drew a parallel between Rousseau’s ideas of the prehistoric human, or ‘the noble savage’, living his/her life in uncorrupted Arcadian bliss with buildings which were free from extraneous and unnecessary ornament. A column in the garden of Eden would carry the weight of a roof and not be merely a decorative ornament.

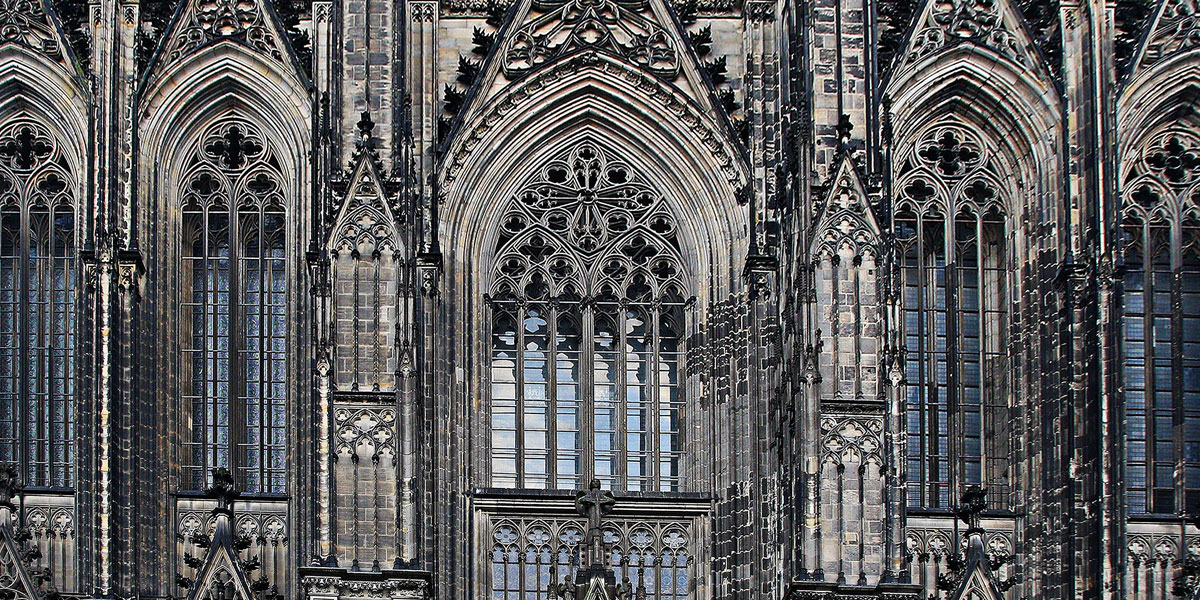

Ruskin and Pugin further developed this argument into the idea that different materials and construction should affect the form of the resulting building. The concept of ‘truth to materials’ was invented. In typical Victorian style, they saw buildings as morally good or bad, based on these notions. Gothic was good, ‘true’ and Christian while Classical was bad, ‘false ‘and pagan. Gothic is a style generated out of the physical performance of materials while classical is a style that comes from an idea of how a building should look and the material is to some extent irrelevant. Ruskin and Pugin’s ideas were essential to the modernist movement and the fetishizing of structure and materials can most obviously be seen in some of London’s most ugly buildings.

This way of judging buildings is so ingrained in architectural thought that it hardly needs to be said and it is very much with us now. Architects routinely talk about ‘structural integrity’ or buildings being ‘honest’ or ‘true’ in a way which probably makes no sense to people outside the profession.

Ruskin and Pugin were right about Classicism, it does not let the materials and construction affect how the building looks. Classicism is about form and proportion in the service of beauty. If you look at the history of the style, classicism uses the same form on a variety of materials. The Triglyph is a classic example, its origin is thought to have come from timber construction with the triglyph as the beam end and the guttae as pegs to hold it in place. This was later copied in stone and used by the ancient Greeks for their Doric temples and all other Doric orders ever since. This form has nothing to do with stone construction, the form itself creates beautiful shadows which work for any material. American classical architects routinely made their cornices out of zinc or copper instead of stone, is a further development of the same idea.

My friend Ruaidhri Tulloch worked on a housing development in Versailles. Unlike the palace, this project had serious cost constraints. In order to fit with the architecture of the town, they followed the generic local style, but they could not afford to use the correct traditional materials. So they built a traditional urban block out of polystyrene with a specialist finish to look like a lime render. Obviously, polystyrene is a dreadful material on so many levels and lime render would have been so much nicer but given that this was not possible, I feel they made the right decision to keep the form as it was, rather than design in a new style to respond to the technical properties of polystyrene.

Trying to create beautiful buildings by simply using construction is like writing a novel and hoping that the correct spelling and grammar are enough to make a good read. But more importantly, the author needs to have something to say, otherwise, their use of language is somewhat pointless. Likewise, an architect must have an intention about how their buildings should look and this cannot be generated simply from how they are made.