Edwardian Classical Architecture in Manchester

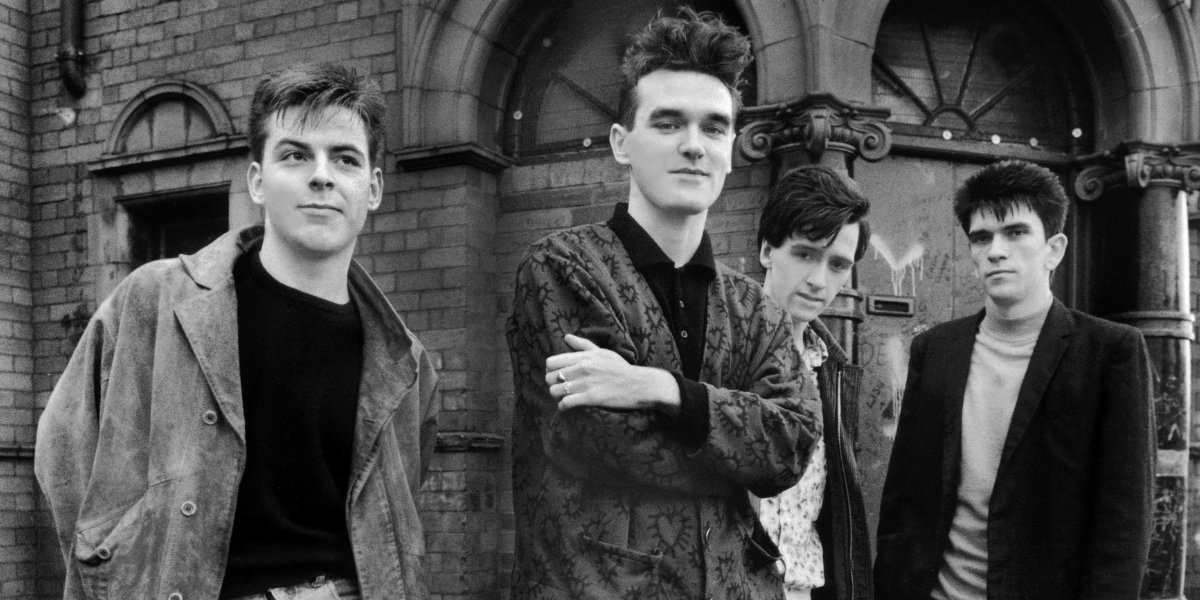

Until recently my knowledge of Manchester architecture was limited to the inside gatefold of ‘The Queen is Dead’ LP. This shows the Smith’s standing outside the Salford Lads Club, where a terracotta Scamozzi Ionic capital can be seen cheekily peaking our over Morissey’s shoulder. I imagined the rest of the city continued in this vein, which indeed it does but with a scale, grandeur and flamboyance I could have only dreamed of.

I was fortunate to visit Manchester recently and if you have a taste for Edwardian Baroque architecture, this is the place to go. I am using the term ‘Edwardian’ to be not just the architecture between 1901 and 1910 but the exuberant and confident spirit which pervaded all the arts from the late Victorian period until the First World War. In music it is Elgar, in painting it is John Singer Sargent and in architecture it is a myriad of unknown practitioners whose creativity and skill would make the Baroque masters of Europe quake in their bucket top boots.

One of the great architects of this period was Alfred Waterhouse (1830- 1905) the architect of the Natural History Museum. He initially set up his practice in Manchester and put his stamp on the city with the Town Hall which was his first major commission. This he designed in Gothic style but as time went on, like his contemporary the painter Edward Millais he became more classical. His Refuge Assurance Building designed in partnership with his son Paul combines various styles from Baroque to Dutch Renaissance to make a building which feels surprisingly unified. It reminded me of Schinkel’s now demolished Bauakademie in Berlin, which similarly combines the warm reds and oranges of brick and terracotta. This colour palette is one of the distinctive features of Manchester architecture and can be seen on relatively modest buildings like the Salford Lads Club as well as the grandest buildings in the city. What gives this building an extra level of vibrancy is the use of green for the copper dome which is echoed in the window joinery and downpipes, particularly the downpipes which are one of the hallmarks of the superb attention to detail that can be seen in all of Waterhouse’s work.

One of the joys of visiting an unfamiliar city is that you inevitably come across brilliant architects you have never heard of. One such individual is the home-grown Mancunian Charles Heathcote (1851-1938) who designed prolifically in a Baroque style. His former Lloyds Bank at 53 King Street in white stone is an essay in shadow casting making the building like an inhabited sculpture. The free-standing ionic columns sit above a lower order of rustication which alternates between smooth and roughly hewn stone. This turns into smooth quoins which continue right up to the chimneys. The corner is beautifully resolved with a mini aedicule with sculpture above.

Also by Heathcote is the former National Westminster Bank in Spring Gardens, built from red sandstone. This, like his Lloyds Bank, makes a virtue of the corner but with a bold arched entrance door framed by octagonal piers and topped with a dome supported by paired ionic columns as buttresses on each corner.

Just down the road from this is the Former Midland Bank by Edwin Lutyens. Serine and white it sits proudly on King Street like the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or a formalised pyramid with its form breaking down and reducing as it ascends. Being both Classical and Art Deco it takes the form of many New York skyscrapers of the time with an ornate ground and top floor with simple windows on the intervening floors. The windows are set far back from the stone face of the wall which gives the building a massive and solid character. This contrasts with the thinness of the Doric pilasters on the ground floor which disappear into the rustication halfway up the shaft. For those who enjoy Sir Ned’s usual architectural tricks there is more than enough to keep you happy.

If you want to know how to do a tower look no further than Lancaster House on Whitworth Street, a former packing and shipping warehouse. Constructed in red brick and orange terracotta designed by Harry S. Fairhurst.

In this area there are a plethora of massive Baroque warehouses many of which were designed by Fairhurst. The detail, scale and ornamentation of these buildings is staggering. It makes me feel slightly frustrated that the current solution to warehousing is massive sheds which the owners are so ashamed of that they try to tone them in with the sky.

Further out of town is the Royal Infirmary on Oxford Road. Designed by Edwin Hall and John Brooke which was significantly opened by King Edward VII - a statue of the jovial king can be seen close by. I had not heard of either architect, although after a little research I discovered that Edwin Hall also designed Liberty & Co’s flagship store and I am very familiar with its Mock-Tudor façade just off Regent’s Street.

Also walking in the outskirts of Manchester I came across Platt Hall, a Georgian country house by Carr of York which sits with its park almost oblivious to the urban sprawl that surrounds it. It is hard to image this estate within fields only a short carriage ride from Manchester. Although this house is by one of the giants of Georgian architecture, it seemed small fry compared to the confident Edwardian buildings of the city centre. There is an attitude in polite society that it you must like classical architecture make sure it’s the refined well-mannered Georgians. Edwardians are thought to be too vulgar, perhaps ‘criminally vulgar’ as Morrissey would say. But how can you not love their playfully unrestrained buildings? I am beginning to think that maybe these relatively unknown architects are the closest British architects come to the genius of Michelangelo and Borromini.

The Edwardian spirit held on in Manchester right until the Second World War, decades after King Edward’s death. The extension to the Town Hall and next to it the Pantheon like Central Library were both built in the 1930s and designed by Vincent Harris (1876- 1971). He was great classical architect who design numerous notable buildings including Sheffield City Hall, Leeds Civic Hall, The Ministry of Defence on Whitehall and Kensington Central Library. He was the last of an era yet somehow won the RIBA Royal Gold Medal in 1951 despite substantial opposition from his modernist contemporaries. On accepting the award Harris is reported to have said: “Look, a lot of you here tonight don’t like what I do and I don’t like what a lot of you do …”

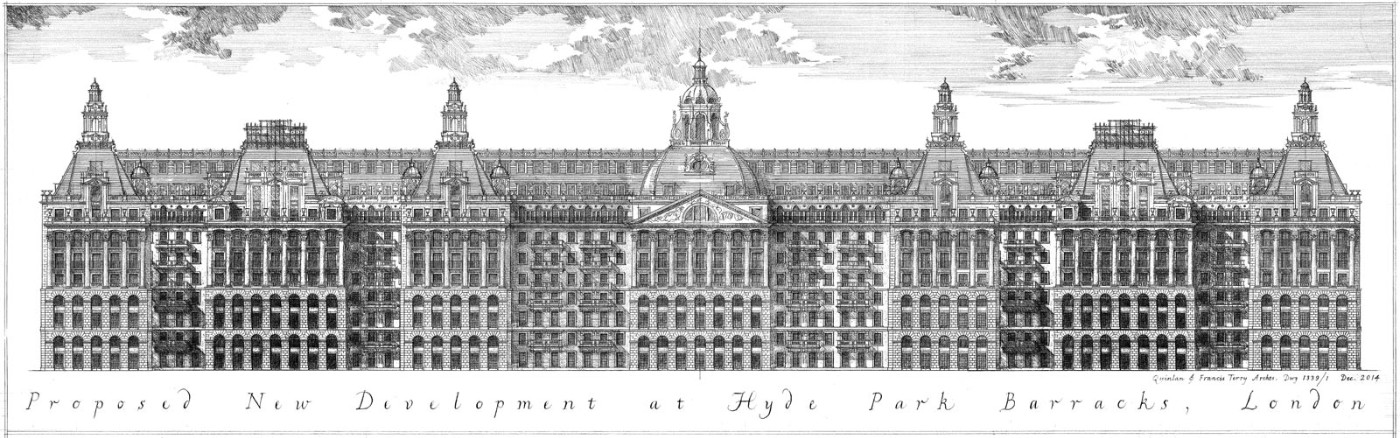

Unfortunately, most of the post war and current architecture is a disaster. It is a pity that Manchester could not continue with the style of Harris, Heathcote, and Fairhurst. It is quite possible to design new Edwardian style buildings, we have the craftsman and the expertise. I designed one of my own a few years ago as a replacement to Knightsbridge Barracks, unfortunately the design never came to fruition, but if an ambitions developer or maybe Mayor Andy Burnham reads this and wants to get in touch, I would be happy to oblige. I will even do the first sketch pro bono.